Hello, I’m Veronica

The sky is not completely dark at night. Were the sky absolutely dark, one would not be able to see the silhouette of an object against the sky.

-

Back in Africa… or Italy?

Johannesburg, le 6 septembre 2022

Bonjour!

En direct de la nation “arc-en-ciel”, pour raconter mes premières heures en Afrique. En format récit de voyage, car ce continent chéri m’inspire à prendre la plume pour consigner ces premières impressions dans un calepin — oui, un vrai de vrai —, celui-là même qui m’accompagnait lors de ce premier voyage ici en 2004 et que j’ai retrouvé par hasard avant de boucler ma vieille valise. Sans boucle mais avec une de ces sangles qui retiendra mes effets au cas où la fermeture éclair choisissait de rendre l’âme exposant ma vie (en boucle) sur un carrousel d’aéroport.

Bref, voyage impeccable sur KLM et la compagnie est exactement la même que lors de mes derniers aller-retour en Afrique. Tout, tout, tout est pareil!! Même décor, même personnel sympathique, même service, même ponctualité, même bouffe: « pasta or chicken? », même syrah sud-africain. Donc, rien à signaler de ce côté.

C’est d’abord l’odeur de la fumée qui me ramène en Afrique. La nuit noire des quartiers où l’électricité est une denrée rare, car trop chère et où le feu la replace.

Du haut des airs, la nuit divise Johannesburg encore plus qu’en plein jour. Une ligne nette démarquant l’affluence ostentatoire de la pauvreté des bidonvilles. Puis, sitôt le pied sur le tarmac et le nez dehors, après l’air recyclé du voyage, c’est la fumée âcre des feux qui réchauffent, nourrissent, éliminent et chassent les insectes. Sur ce continent et dans ce pays, les contrastes sont délimités par des barbelés et des policiers armés d’AK-47.

Pas l’Afrique reposante ici et je suis touriste dans la démesure. Pas une Afrique que je connais bien et, en cette première matinée à errer sans but, je peine à comprendre les codes.

Le trajet d’une vingtaine de minutes depuis l’aéroport dans un taxi préalablement réservé et sur une autoroute quasi déserte en soirée ne m’a rien révélé sur mon emplacement dans cette ville. Le panneau à la sortie indiquait Sandton, quartier cossu pas trop loin du centre de conférence et du bureau des collègues de Mark.

La nuit a été salutaire dans un lit douillet et l’hôtel dans lequel je loge aux frais de la princesse, se trouve dans complexe qui héberge un casino.

Parcours découverte ce matin et je constate que c’est bien pire que l’horreur commerciale à laquelle m’avait préparée Mark.

Il est 10h30 et j’ai l’impression d’être replongée dans la nuit. Sans fumée cette fois. Des artifices et un scintillement tape-à-l’oeil pour recréer une idée de ce que devrait être l’Italie. (Notez l’ombre de la cheminée sur le ciel dans la première photo.)

Quand à Rome… je commande un latte au comptoir d’un café où se trouve un clavier sur lequel on me demande de saisir mon numéro. « What number ?», que je demande. « Phone number Mama ». Ah. Avec ou sans symbole du plus devant le code pays? « What do you mean country Mama, you no from here? », me demande-t-elle. « No, I’m from Canada ». Sur quoi elle répond, « take me with you ».

De ma table, j’observe le gars du resto grec d’en face sortir jéroboam, Nabuchodonosor et autres bouteilles vides qui ornent sa devanture. La jeune fille qui m’a servie vient s’asseoir à ma table pour faire un brin de jasette, me dit qu’elle vient du Zimbabwe, qu’elle est au pays depuis sept ans. Je lui demande comment elle trouve ça travailler dans un décor où c’est toujours la nuit. Elle adore me dit-elle, enchaînant avec la formule racoleuse de la pub : « No need to go to Italy! ». Je lui dit que selon ce que j’en sais l’Italie c’est lumineux et ensoleillé, pas couvert d’un plafond noir ou peint en faux nuages.

« Take pictures », me dit-elle quand je lui dis que je vais aller voir les chutes de Victoria la semaine prochaine. Je la rassure et lui dis que je compte bien en prendre.

En attendant, j’en ai pris de cette Italie artificielle qui sent le désinfectant et où les bistros et établissements de restauration rapide, le casino, les cinémas, les boutiques et centres de divertissements rivalisent pour attirer une rare clientèle matinale.

J’avoue que c’est une sacrée bonne représentation de l’idée que je me fais de l’enfer.

Le Bird Sanctuary était fermé aujourd’hui. Demain, je visite le Berceau de la civilisation. Enfin, un des berceaux, car depuis, on en a découvert d’autres. J’espère qu’il sera moins clinquant que leur Italie.

Ciao! A domani!

-

-

When wanting to give back is not enough

When wanting to give back is not enough

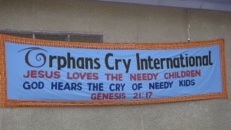

This way to the orphanage

I was at the wheel of my trusted steed, a 1995 Land Rover Defender, which my partner and I had driven from the U.K. to Takoradi, a coastal town in the Western Region of Ghana where we had chosen to settle in early 2006.

Parked in a field, just off the Agona Road near Apowa village, I was waiting for Nicki, another obruni from the U.K. The term obruni is used throughout Ghana to call the ‘white man’ or foreigners in general. Visitors in Ghana are commonly asked: “Hey obruni, where are you going?” We had arranged to meet so that she could show me the way to an orphanage with the unfortunate name of Orphans Cry International at which she was a self-appointed volunteer teacher. Nicki wanted to introduce me to the children and their carers and was keen for me to help her out in any way I could. I was loath to get dragged into yet another project as I felt I had a lot on my plate already; I was Cultural Events Manager for the Alliance Française (an equivalent to the British Council or the Goethe-Institute, the Alliance Française — or AF — is present in 135 countries and its aim is to promote French language and culture worldwide) and Regional Warden for the Canadian High Commission, I taught a weekly aqua fitness class, I co-founded and managed a Book Club and a Film Club, I was on the board of directors of a private members’ club and I was trying to run a business. Apart from my own venture — nomadafrik farms — all of these undertakings were, of course, not remunerated. Being part of an expatriate community means that putting forward the plan for a potential activity to a group often results in becoming the organiser of said activity. What’s more, anyone showing signs of being the least bit competent at getting something organised immediately becomes the go-to person whenever something needs to be done. Thus, I found myself baking cakes for christenings, being a decorator and party organiser and throughout, managed to gather an impressive database of contacts. Hence, my appeal to Nicki. I had told Nicki that, firstly, I didn’t “do kids” mainly because I knew I would find it difficult not to get emotionally involved. Secondly, as I’ve already mentioned, I had no time left to devote to her or to the orphanage. In spite of this, not only was she still intent on me joining her that day, but she was also very good at drawing me in further that I ever imagined I would ever want to go. Since then I have become much better at saying “no” and meaning it. At least, I like to think so.

Parked in a field, just off the Agona Road near Apowa village, I was waiting for Nicki, another obruni from the U.K. The term obruni is used throughout Ghana to call the ‘white man’ or foreigners in general. Visitors in Ghana are commonly asked: “Hey obruni, where are you going?” We had arranged to meet so that she could show me the way to an orphanage with the unfortunate name of Orphans Cry International at which she was a self-appointed volunteer teacher. Nicki wanted to introduce me to the children and their carers and was keen for me to help her out in any way I could. I was loath to get dragged into yet another project as I felt I had a lot on my plate already; I was Cultural Events Manager for the Alliance Française (an equivalent to the British Council or the Goethe-Institute, the Alliance Française — or AF — is present in 135 countries and its aim is to promote French language and culture worldwide) and Regional Warden for the Canadian High Commission, I taught a weekly aqua fitness class, I co-founded and managed a Book Club and a Film Club, I was on the board of directors of a private members’ club and I was trying to run a business. Apart from my own venture — nomadafrik farms — all of these undertakings were, of course, not remunerated. Being part of an expatriate community means that putting forward the plan for a potential activity to a group often results in becoming the organiser of said activity. What’s more, anyone showing signs of being the least bit competent at getting something organised immediately becomes the go-to person whenever something needs to be done. Thus, I found myself baking cakes for christenings, being a decorator and party organiser and throughout, managed to gather an impressive database of contacts. Hence, my appeal to Nicki. I had told Nicki that, firstly, I didn’t “do kids” mainly because I knew I would find it difficult not to get emotionally involved. Secondly, as I’ve already mentioned, I had no time left to devote to her or to the orphanage. In spite of this, not only was she still intent on me joining her that day, but she was also very good at drawing me in further that I ever imagined I would ever want to go. Since then I have become much better at saying “no” and meaning it. At least, I like to think so.So, it was 2007 and I was parked at, or near enough by African bush standards, the appointment rendezvous location. While I waited, I watched a group of five young men approaching in my wing mirror. Like most local men aged between 15 and 25 in rural areas, they were lean, strong, boisterous and they were “armed” with machetes. I suddenly thought that, had I been living in any number of hot spots on this often volatile continent, the same image would have filled me with dread and panic. But this was Ghana, where the machete — or cutlass as it is locally referred to here — is a tool used by all, even very young children, to cut the grass at school, to cut through the bush or to crack open a coconut. I was a lone woman, at the wheel of her car, in an empty field staring at a potential group of warriors, yet I felt I was safe. In fact, I distinctly remember thinking, at that particular moment, that life was pretty good; the sun was shining and there were far worse places to be, namely stressing through a daily commute in a grey city somewhere. The men walked past my car, the usual greetings were exchanged, they laughed at my use of their language and they went on their way. I looked back at my wing mirror again and spotted a cloud of red dust which announced Nicki’s arrival.

At the time of my first visit, Orphans Cry International (OCI) cared for approximately 40 children between the ages of 2 and 17 years. They did on occasion take in children younger than 2. The compound consisted of a house, where the coordinator lived, a kitchen, girls’ and boys’ dorms and a large multifunctional room used for classes, meetings and church services. There were no doors nor windows to that room and when the rains came in late spring and early fall, torrents of muddy water ran through the building. Otherwise, pigmy goats, chickens and bush dogs came and went as they pleased throughout the day. Three women held the positions of cook, “mother” and teacher and a man, who was called Brother Seth, seemed to spend all his time running around caning the children. I think he was also meant to be a teacher but punishment was more his thing. Caning is commonly and consistently used in Ghana, where advocates against corporal punishment don’t seem to have much of a voice. According to Unicef Ghana, 90% of children in Ghana admit to being victims of violence and I would expect caning is partly responsible for such a high percentage. I have seen with my own eyes a man being spanked by a police officer in Kumasi for jaywalking. It was the funniest thing; the police officer catches this man by the arm and whacks him on the bum, as you would’ve seen an overwhelmed parent do at a time when most parents administered that kind of correction on their progeny. I wondered if the risk of a good walloping might work better than fines elsewhere.

The orphanage was an NGO set up by a local couple, Bishop Emmanuel Young and his wife, the Reverend Mary B. Young. They were rarely present, as they seemed to spend most of their time living in the U.S. where they preached and raised money for the care of the kids. According to the West African Civil Society Institute (WACSI) Organisations Directory, OCI’s Key Objectives aimed: “To establish, own and operate orphanages, teen mother homes, schools of colligate (sic). To train people to trade.”

While Bishop Young and his wife, the Reverend Young, were away their daughter Vivien — who held the position of coordinator at OCI — ran the place. Everybody called her ‘Sister Vivien’ and, when her mother was in town, the kids and staff referred to the Reverend as ‘Grandma’. The Bishop visited once or twice a year. Apart from the regular staff, the orphanage welcomed the odd travelling volunteer (voluntourist) who spent their time there looking after the children, teaching some classes, maintaining the buildings and/or helping with the fundraising.

I’m not quite sure where the volunteers came from because there didn’t seem to be any formal programme in place to welcome a regular stream of them. Organisations such as Projects Abroad or Global Volunteers recruit and send travellers seeking “adventure” and a “lifetime experience” to Ghana and elsewhere in the developing world, but I don’t remember any volunteer I met at OCI ever mentioning a particular organisation. From what I gather, the ones who ended up there had either contacted the Bishop directly or had arranged their placement through local contacts. Or perhaps a lesser-known organisation of this type had brokered their placement.

Voluntourism on the rise

According to a 2012 report in the journal Africa Insight volunteering occupies a large portion of the $173-billion global youth travel industry. The report also mentioned that, at the time of writing, there were “451 organisations offering 2,070 programmes in Africa”. So I wouldn’t be surprised if some obscure gap-year volunteer agency had sent them.

Well-off, mostly white, middle-class gap-year students spending thousands of dollars to go do something ‘worthwhile’ can be found in almost any part of Africa. In Ghana, you bump into these kids everywhere; they have had their hair braided, have bought a drum or are wearing various items of clothing made with colourful African prints and they end their stint in the community or the project they have been sent to by binge-drinking and getting sunburnt at beach resorts on the southern coast of Ghana. Friends who owned a lodge on the beach mostly frequented by these groups thrived, as long as they didn’t run out of beer.

Apart from their enthusiasm and an appetite for adventure, gap-year volunteers often have very few skills to apply to their position. During my time in Ghana, between 2006 and 2011, I met several volunteers and, save a handful of them, the majority had no idea of what they were doing, nor did their presence have much of a lasting effect. Typically aged between 18 and 22, these volunteers are inexperienced, have little knowledge of the country they are going to and receive limited instruction of its culture, let alone its languages. Apart from those who’ve left home to study at college or university, most of them still live with their parents. In any case, it’s probably safe to assume that their financial, emotional and domestic needs are being met by doting parents who will probably be worried sick while their offspring are away.

The aspiring volunteers have convinced Mum and Dad to let them go with the help of the organisations that have recruited them in exchange for some money and zero prerequisite. This is a project of a lifetime from which there is much experience to be gained, namely by doing something worthwhile, enriching a résumé, making lifetime friends, learning a new culture and new skills, etc. (Projects-Abroad.ca/webinar). In spite of being worried, the parents will be proud of their children for wanting to give something back to some poor kids in the developing world.

The question is — or should be — are these volunteers really needed where they are sent and what is the impact of their presence within these communities? In this case, the voluntourism that is of particular concern is that which places an underprivileged child in the direct care of a inexperienced young adult, not that which deals with counting turtles or erecting buildings. In fact, it is in this instance that notions of Western imperialism and lingering colonialism are most obvious. The West, the developed world, has the knowledge, the ability and the right to send unskilled volunteers to go gawk and “experience” poverty, to go develop communities, which are obviously incapable of developing themselves on their own. How very condescending.

In Ghana you have the chance to make a real difference in the lives of orphans and disadvantaged children. We work in several orphanages and care centres in all five regions helping staff to provide the attention, interaction and play that children need. Volunteers can improve the quality of life for children by spending time with them and assisting in their formal and social education. For those with a special interest, we also work at a centre for children with hearing impairments.

Projects-Abroad 2013 Brochure

I was an obruni in Ghana with some experience, potential resources — both material and financial — a network of other fortunate obrunis whose resources I could eventually tap into, an acquired-though-limited understanding and full respect for the subtleties of local cultural traditions and beliefs, a knowledge of the country’s administrative mazes, etc. Yet, in spite of all this, I never once fooled myself in thinking that I would ever be able to “make a real difference” in the lives of the OCI kids. The money I gave Nicki so that little Grace could get surgery to correct clubbed feet might be the only exception. But otherwise, I was lucid enough to realise that I might be giving myself a good conscience but I wasn’t doing anything really worthwhile.

When reading the comments on the websites of the recruiting organisations, I find it somewhat dismaying — if only just because, after all, I am a cynic at heart — that the volunteers never seem to ponder over the effects their presence might have had on the children they were entrusted with or the communities they visited. In line with what they were promised by the organiser, testimonials focus on what was gained or felt from the experience:

I felt very much at home here and enjoyed spending time with her daughter Hannah who kindly taught me how to wash my clothes by hand!

Victoria M.My only regret at the end of the best two months of my life was that I did not stay longer and experience more of the weird and wonderful Ghanaian culture and lifestyle.

Mark B.What surprises me in Ghana is that at school they sometimes make use of the cane to hit children. I found that difficult to see and didn’t use it myself.

Rowena K.More recently, a young woman named Pippa Biddle posted a text on her blog in which she recounts her own “voluntourist” experience in a community building project in Tanzania, with an emphasis on the futility of the impact these kids can hope to have on communities where they are sent. The following excerpt is enlightening:

Our mission while at the orphanage was to build a library. Turns out that we, a group of highly educated private boarding school students, were so bad at the most basic construction work that each night the men had to take down the structurally unsound bricks we had laid and rebuild the structure so that, when we woke up in the morning, we would be unaware of our failure. It is likely that this was a daily ritual. Us mixing cement and laying bricks for 6+ hours, them undoing our work after the sun set, re-laying the bricks, and then acting as if nothing had happened so that the cycle could continue.

I can’t help but think of the local men and what they make of these obruni kids who have paid at least $3,000 — an amount they might not see in a lifetime — to play at laying bricks. It reminds me of the time I had decided to paint a room in our house in Ghana. My garden and security staff were highly amused to see me mixing paint and wielding a paintbrush as they thought I had decided to improvise myself as a painter. It never occurred to them that I would know how to paint because I was not a painter by trade. In their mind, without any formal training or an apprenticeship under the watchful eye of a master, one should make no pretence to being a tradesperson. So to paint you need a painter; to build a chicken coop you need a carpenter; and to build a wall you need a mason. Basically, if you don’t have the skill, you shouldn’t even be entitled to use the tools. It’s as simple as that. The more I think about it, the more I am inclined to agree when it comes to all those volunteers sent to care for children in the developing world: if you’re not trained to deal with disadvantaged children, you shouldn’t be allowed to go near them.

Not only is it worrying that proper vetting processes or police checks don’t seem to be required for the volunteers who work closely with children, but the inability to recognise signs of trauma or abuse can have serious consequences. For the child who suffers at the hand of a relative or his or her carers, how useful is it to have an obruni occupying the respected role of teacher, who sees nothing? It took Nicki — a trained educator and a very astute, sometimes overly empathetic person — months to realise what was really going on at OCI.

The reality of OCI

Culturally, orphanages in Ghana are mainly a “new” thing. There is hardly a use for residential homes for children because traditionally, orphaned children are taken in by their extended family or by another family in their community. A few ruthless Ghanaian entrepreneurs have sniffed out a money-making opportunity by opening orphanages and offering to buy children from desperate parents, who feel they cannot provide for their brood. The parents are promised wonderful things for their child and view the transaction as a fruitful opportunity for the whole family. They often believe they will be reunited with the child they have traded once their situation improves. In Ghana, child labour and trafficking are very much a reality in spite of government efforts to address the situation. Unicef Ghana reports the recent implementation of a moratorium that aims to ban all child adoptions. The difficulty in Ghana lies not with applying new initiatives, but rather with their enforcement.

It turns out that a number of the children at OCI were not actually orphans. Some had one parent, some had both, and there were those who had relatives living in other regions who could have taken them in. When Nicki first started visiting OCI in the autumn of 2007, the orphanage Coordinator and Grandma stated they did not have a register of the children who were in their care. Even by Ghanaian standards, the unavailability of records, the lackadaisical administration of care, the restricted access to formal education and the poor living conditions were a disgrace. Over the next few months, it became clear that all was not well under the sun and that children at OCI came and then disappeared and those who were there suffered from abuse.

It turns out that a number of the children at OCI were not actually orphans. Some had one parent, some had both, and there were those who had relatives living in other regions who could have taken them in. When Nicki first started visiting OCI in the autumn of 2007, the orphanage Coordinator and Grandma stated they did not have a register of the children who were in their care. Even by Ghanaian standards, the unavailability of records, the lackadaisical administration of care, the restricted access to formal education and the poor living conditions were a disgrace. Over the next few months, it became clear that all was not well under the sun and that children at OCI came and then disappeared and those who were there suffered from abuse.In February 2009, it was announced that the Ghana Department of Welfare ordered the closing down of the Orphans Cry International based on reports of “unlawful adoption, immoral acts, sexual harassment, emotional abuse and maltreatment”.

In light of this, the question I pose is what does the 18- to 22-year-old student volunteer described above have in his or her experiential backpack that will equip him or her to deal with a child who has been — and continues to be — physically or sexually abused whilst in residential care? As ex-voluntourist Pippa Biddle concedes, she and her fellow volunteers “failed at the sole purpose of [their] being there” and that observation pretty much sums up what the voluntourism industry appears to be: ludicrously useless to those it is striving to help.

Consider this

When OCI was ordered to close down, the children were either sent back to their families or relatives, integrated into foster families, or they were given places at boarding schools, which were supported by members of the expatriate community. I don’t know how many “voluntourists” spent time at the orphanage over the years it was in operation and I wonder if — apart from only one person I know of —many of them noticed things were amiss. If any of them did, were efforts ever made to denounce the situation? I think it is time the business of sending unskilled volunteers to care for children in the developing world be seriously reconsidered. Would any parent in the Western world ever entrust his or her child to be cared for and educated by an unskilled young volunteer from Ghana if we were to reverse the tables? Would we be accepting of all these kids coming to teach our children and show us how to do things? Somehow, I don’t think so.

About Me

The sky is not completely dark at night. Were the sky absolutely dark, one would not be able to see the silhouette of an object against the sky.

Follow Me On

Subscribe To My Newsletter

Subscribe for new travel stories and exclusive content.